1.失踪

凌晨12点42分 在2014年3月8日安静的月夜,由马来西亚航空公司运营的波音777-200ER从吉隆坡起飞并转向北京,攀升至其指定的35,000英尺的巡航高度。马来西亚航空公司的指定人员是MH。航班号是370.副驾驶Fariq Hamid正在驾驶飞机。他27岁。这是他的最后一次训练飞行;他很快就会完全获得认证。他的教练是指挥官,一名名叫Zaharie Ahmad Shah的男子,他53岁时是马来西亚航空公司最资深的上尉之一。在马来西亚风格中,他以他的名字Zaharie而闻名。他结婚了,有三个成年子女。他住在一个门控开发中。他拥有两栋房子。在他的第一所房子里,他安装了一个精心制作的微软飞行模拟器。他经常飞行,经常在网上论坛上发布他的爱好。在驾驶舱里,法里克本来会对他表示恭敬,但扎哈里并不以霸道而闻名。

要听更多专题报道, 获取Audm iPhone应用程序。

在机舱内有10名乘务员,他们都是马来西亚人。他们有227名乘客需要照顾,其中包括5名儿童。大多数乘客都是中国人;其余的38人是马来西亚人,其他人来自印度尼西亚,澳大利亚,印度,法国,美国,伊朗,乌克兰,加拿大,新西兰,荷兰,俄罗斯和台湾。那天晚上在驾驶舱内,当Fariq副驾驶飞机时,Zaharie上尉处理了收音机。这种安排是标准的。 Zaharie的传输有点不同寻常。凌晨1点01分,他通过无线电广播说他们已经在35,000英尺处稳定下来 – 这是一个在雷达监视空域的多余报告,其中规范是报告离开高度,而不是到达一个高度。 1:08飞越马来西亚海岸线,越过南中国海向越南方向飞去。 Zaharie再次报告该飞机的水平为35,000英尺。

十一分钟后,当飞机在越南空中交通管辖区附近的一个航点上关闭时,吉隆坡中心的管制员通过无线电广播说:“马来西亚三七零,请联系胡志明一二零小数 – 九。晚安。“Zaharie回答说,”晚安。马来西亚三七零。“他没有像他应该的那样回读频率,但是否则传输听起来是正常的。这是世界上最后一次听到MH370的消息。飞行员从未与胡志明登记或回答任何随后的提升他们的尝试。

更多故事

初级雷达依赖于天空中物体的简单原始砰砰声。空中交通管制系统使用所谓的二级雷达。它取决于每架飞机发送的转发器信号,并包含更丰富的信息 – 例如,飞机的身份和高度 – 而不是主雷达。在MH370进入越南领空五秒后,代表其转发器的符号从马来西亚空中交通管制的屏幕上掉落,37秒后整架飞机从二级雷达上消失。时间是起飞后39分钟凌晨1点21分。吉隆坡的控制器正在处理屏幕上其他地方的其他交通,根本没有注意到。当他最终做到时,他认为飞机在胡志明手中,超出了他的射程范围。

与此同时,越南管制员看到MH370进入他们的领空,然后从雷达上消失。他们显然误解了胡志明应该立即通知吉隆坡的正式协议,如果已经交出的飞机迟到超过五分钟,他们会立即通知吉隆坡。他们多次尝试联系飞机,但无济于事。当他们拿起电话通知吉隆坡时,MH370从他们的雷达屏幕上消失了18分钟。随之而来的是混乱和无能的运动。吉隆坡的航空救援协调中心应在失踪后一小时内得到通知。到凌晨2:30,它仍然没有。在紧急响应最终开始之前还有4个小时,时间是早上6点32分。

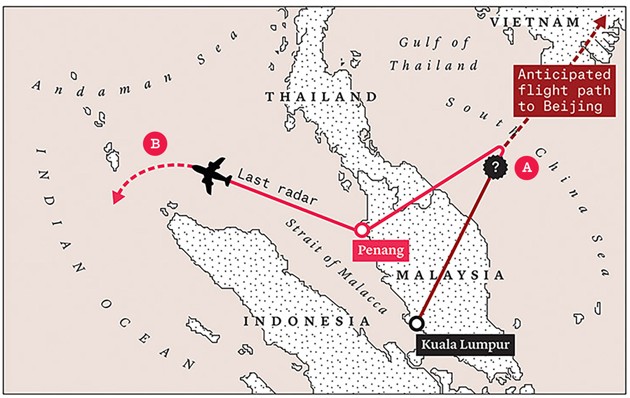

那一刻,飞机本应该降落在北京。寻找它最初集中在马来西亚和越南之间的南中国海。这是来自七个不同国家的34艘船和28架飞机的国际努力。但MH370远不及那里。在几天之内,从空中交通管制计算机中抢救出的主要雷达记录,以及秘密马来西亚空军数据的部分证实,显示MH370一旦从二级雷达上消失,它就急剧转向西南,飞回来横跨马来半岛,并在槟城岛周围堆积。它从那里向西北飞到马六甲海峡,越过安达曼海,在那里它越过雷达范围,变得模糊不清。这部分飞行需要一个多小时才能完成,并表明这不是劫持的标准情况。也不像以前任何人遇到过的事故或飞行员自杀情景。从一开始,MH370就是未开发方向的主要研究人员。

围绕MH370的谜团一直是继续调查的焦点,也是有时狂热的公众猜测的根源。这次损失摧毁了四大洲的家庭。具有现代仪器和冗余通信的复杂机器可能完全消失的想法似乎超出了可能性范围。很难永久删除一封电子邮件,即使有意进行尝试,离开网格也几乎无法实现。波音777应始终以电子方式使用。飞机的消失引发了许多理论。许多是荒谬的。所有人都被赋予了生命,因为在这个时代,商用飞机不仅仅会消失。

这一次确实如此,五年多以后,它的确切下落仍然未知。即便如此,关于MH370消失的大量内容已经变得更加清晰,重建当晚发生的大部分事情都是可能的。驾驶舱录音机和飞行数据记录器可能永远无法恢复,但我们仍然需要知道的不太可能来自黑匣子。相反,它必须来自马来西亚。

2.巨浪

在晚上 飞机失踪后,一名名叫布莱恩吉布森的中年美国男子正坐在已故母亲在加利福尼亚州卡梅尔的家中,整理她的事务以准备出售物业。他在CNN上听到有关MH370的消息。

吉布森,我最近在吉隆坡遇到的,是一名受过培训的律师。他在西雅图生活了35年以上,但在那里度过的时间很少。他的父亲几十年前去世,是一名第一次世界大战的老兵,他在战壕中遭受了芥子气袭击,获得了银星奖,并且继续担任加州首席大法官超过24年。他的母亲毕业于斯坦福大学法学院,是一位热心的环保主义者。

吉布森是独生子女。他的母亲喜欢国际旅行,她带着他。在7岁时,他决定他的生活目标是至少访问世界上每个国家一次。最终,这挑战了定义 访问 和 国家但他坚持完成任务,放弃任何持续职业生涯的机会,并依靠适度的继承。根据他自己的说法,他一路上涉及一些着名的奥秘 – 危地马拉和伯利兹丛林中的玛雅文明的结束,西伯利亚东部的通古斯流星爆炸,以及山中的盟约方舟的位置。埃塞俄比亚。他打印出了自己的卡片: 冒险家。探险家。真像探寻者。 他穿着一顶浅顶软呢帽,就像印第安纳琼斯一样。当消息传来MH370的消失时,他很容易引起注意。

尽管马来西亚官员反身拒绝,马来西亚空军彻底混淆,但飞机奇怪的飞行路径的真相很快就开始浮出水面。事实证明,在飞机从二级雷达消失后,MH370继续间歇性地与伦敦商业供应商Inmarsat运营的地球静止印度洋卫星连接6小时。这意味着飞机没有突然遭遇一些灾难性事件。在这6个小时内,人们认为它仍然处于高速,高空巡航飞行中。 Inmarsat连接,其中一些被称为“握手”,是电子短信:常规连接相当于最低限度的通信耳语,因为系统的预期内容 – 乘客娱乐,驾驶舱文本,自动维护报告 – 已被隔离或关掉了。总而言之,有七个连接:两个由飞机自动启动,另外五个由Inmarsat地面站自动启动。还有两个卫星电话;他们没有得到答复,但提供了额外的数据。与大多数这些连接相关联的是Inmarsat最近才开始记录的两个值。

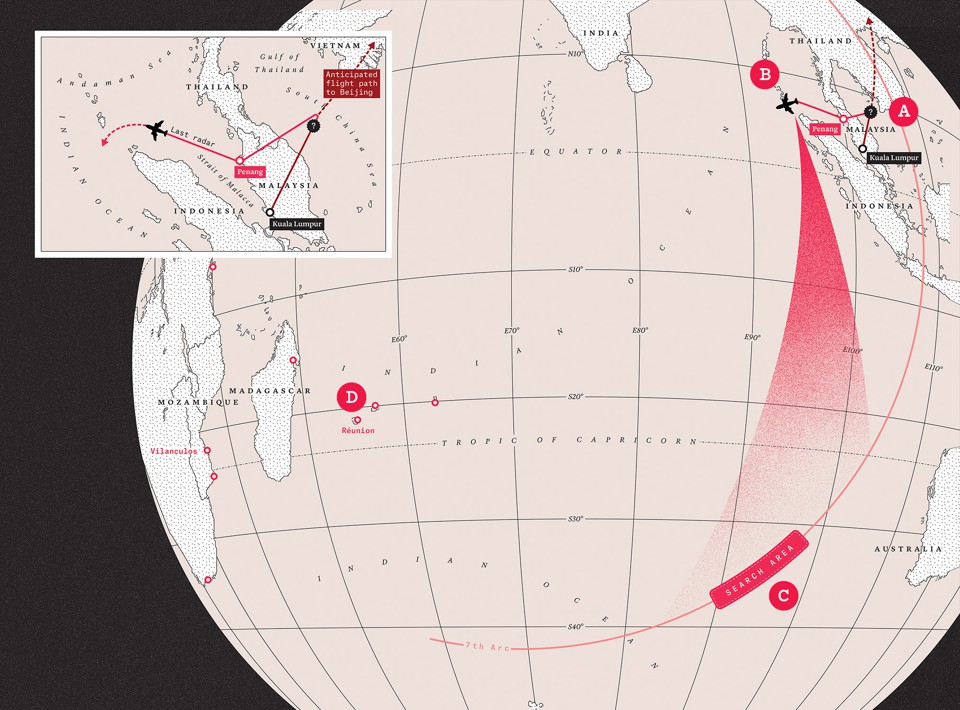

第一个和更准确的值被称为突发定时偏移,或称为“距离值”。它是飞机的传输时间的度量,因此是飞机距离飞机的距离的度量。卫星。它没有精确定位单个位置,而是所有等距位置 – 大致圆形的可能性。考虑到MH370的范围限制,近圆可以减少为弧形。最重要的弧线是第七个也是最后一个 – 由最终的握手定义,以最复杂的方式捆绑,以消耗疲劳和主发动机的故障。第七弧从北部的中亚延伸到南部的南极洲附近。 MH370于吉隆坡时间早上8点19分穿过。可能飞行路径的计算将飞机的交叉点与第七个弧线相交 – 因此它的终点 – 如果飞机向北转向哈萨克斯坦,或者如果它向南转向则在南印度洋。

技术分析表明飞机已经接近南方。我们从Inmarsat的第二个记录值 – 突发频率偏移中知道这一点。为了简单起见,我将这个值称为“多普勒值”,因为它最重要的是包括与卫星位置相关的高速运动相关的射频多普勒频移,并且是自然的飞机上飞机卫星通信的一部分。必须通过机载系统预测和补偿多普勒频移,以使卫星通信起作用。但是补偿并不是很完美,因为卫星 – 特别是随着它们的老化 – 不会按照飞机编程预期的方式传输信号。它们的轨道可能略微倾斜。它们也受温度影响。这些缺陷留下了明显的痕迹。虽然以前从未使用多普勒频移测井来确定飞机的位置,但伦敦的Inmarsat技术人员能够辨别出一个显着的扭曲,表明在凌晨2点40分转向南方。转折点位于北部和西部的一个地方。苏门答腊岛,印度尼西亚最北端的岛屿。在一些分析风险的情况下,假设飞机在南极洲的大方向上直飞并水平很长时间,超出了它的射程范围。

六小时后,多普勒数据显示陡峭的下降 – 比正常下降率高五倍。在穿过第七弧的一两分钟内,飞机潜入海中,可能在撞击前脱落部件。从电子证据来看,这不是对水上降落的控制尝试。飞机必须立即破碎成一百万件。但没有人知道影响发生在哪里,更不用说为什么了。并且没有人有一点物理证据证实卫星解释是正确的。

失踪后不到一周, 华尔街日报 发布了关于卫星传输的第一份报告,表明这架飞机在沉默后很可能在高空停留数小时。马来西亚官员最终承认该说法属实。据说马来西亚政权是该地区最腐败的政权之一。它在飞行调查中证明自己是鬼鬼祟祟,恐惧和不可靠。从欧洲,澳大利亚和美国派遣的事故调查人员对他们遇到的混乱感到震惊。由于马来西亚人隐瞒了他们所知道的东西,最初的海上搜查集中在错误的地方 – 南中国海 – 并且没有发现漂浮的碎片。如果马来西亚人立即说出真相,可能会发现这些碎片并用于识别飞机的大致位置;黑匣子可能已被找回。水下搜索它们最终集中在数千英里外的狭窄海域。但即使是一片狭窄的海洋也是一个很大的地方。花了两年时间才找到法国航空公司447的黑匣子,这些黑匣子在2009年从里约热内卢飞往巴黎的大西洋上坠毁到了大西洋 – 搜索者确切知道在哪里看。

经过近两个月徒劳的努力,最初的地表水搜索于2014年4月结束,焦点转移到海洋深处,现在仍然存在。布莱恩吉布森一开始就是从远处沮丧。他卖掉了他母亲的房子,搬到了老挝北部的金三角,在那里他和一个商业伙伴开始在湄公河上建一家餐馆。他加入了一个致力于损失MH370的Facebook讨论组。它充满了猜测,但也有新闻反映了有关飞机可能发生的事情以及可能发现主要残骸的地方的有用思考。

虽然马来西亚人名义上负责整个调查,但他们缺乏进行海底搜索和恢复工作的手段和专业知识;作为优秀的国际公民,澳大利亚人起了带头作用。卫星数据所指的印度洋地区 – 珀斯西南约1200英里 – 是如此之深和未开发的 第一个挑战是绘制海底地形图 足以允许侧扫扫描声纳车辆在地面下方安全地拖曳数英里。海底有黑色的山脊,光线从未穿过。

吉布森开始怀疑,对于所有艰苦的水下搜索,飞机上的碎片是否有一天可能只是在某个地方的海滩上冲洗。在访问柬埔寨海岸的朋友时,他问他们是否偶然发现了什么。他们没有。碎片不可能从南印度洋漂流到柬埔寨,但直到飞机的残骸被发现 – 证明南印度洋确实是它的坟墓 – 吉布森决心保持开放的心态。

2015年3月,乘客的近亲在吉隆坡举行了为期一年的MH370失踪纪念活动。不请自来,并且很大程度上不了解他们,吉布森决定参加。因为他没有特别的知识,所以他的到来引起了人们的注意。人们不知道该怎么做一个dilettante。纪念活动在一个购物中心的户外空间举行,这是吉隆坡的典型活动场所。目的是集体悲痛,但也要保持马来西亚政府的压力,以提供解释。数百人参加,其中许多人来自中国。舞台上有一些音乐。在背景中,一张大型海报展示了波音777的轮廓以及文字 哪里, 谁, 为什么, 什么时候, 谁, 怎么样,并且 不可能, 史无前例, 消失,和 无知。主要发言人是一位名叫Grace Subathirai Nathan的年轻马来西亚女子,她的母亲曾在飞行途中。内森是一名专门从事死刑案件的刑事辩护律师,其中马来西亚因严厉的法律而有很多。她已成为近亲的最有效代表。她带着一件印有MH370卡通图案的超大T恤和劝告走上舞台 搜索然后继续描述她的母亲,她对她的深切爱,以及忍受失踪的困难。有时她会像观众中的一些人一样静静地哭泣,包括吉布森。之后,他走近内森,问她是否愿意接受陌生人的拥抱。她做了,他们成了朋友。

吉布森离开了纪念活动,决定通过解决他所认为的缺口 – 缺乏沿海搜寻浮动碎片的帮助。这将是他的利基。他将成为MH370的私人泳滩。官方调查员,主要是澳大利亚人和马来西亚人,在水下搜索方面投入了大量资金。他们本可以嘲笑吉布森的雄心壮志,正如他们嘲笑数百英里之外的海滩,吉布森会找到飞机的碎片。

3.母亲Lode

印度洋 根据您计算中包含的岛屿数量,对数万英里的海岸线进行清洗。当布莱恩吉布森开始寻找碎片时,他没有计划。他飞到了缅甸,因为无论如何他都打算去那里,然后去了海岸,并向一些村民询问漂流物往往漂流上岸。他们把他带到了几个海滩,一名渔夫乘船到那里。他发现了一些碎片,但没有任何来自飞机的碎片。他建议村民们留意,留下他的联系电话,继续往前走。同样,他在没有发现感兴趣的碎片的情况下访问了马尔代夫以及罗德里格斯和毛里求斯岛屿。然后是2015年7月29日。飞机失踪后大约16个月,法国留尼汪岛上的一个市政海滩清理人员 发现了一片破碎的翼型 大约六英尺长,似乎刚冲上岸。机组人员,一个名叫JohnnyBègue的人,意识到它可能来自一架飞机,但他不知道哪一架。他简单地考虑将它放入相邻草坪上的纪念场所并在其周围种植一些鲜花 – 但他却把这个新闻称为当地广播电台。一队宪兵出现并把这件事拿走了。它很快被确定为波音777的一部分,这是一个称为襟副翼的控制面,附着在机翼的后缘上。随后对序列号的检查表明 它来自MH370。

这是已经电子推测的必要物理证据 – 飞行在印度洋猛烈地结束了,尽管在留尼旺以东数千英里的地方仍然是未知的。飞机上的人的家人不得不放弃任何他们的亲人可能还活着的幻想。无论他们多么理性和现实,这都令人震惊。 Grace Nathan被摧毁了。她告诉我,在发现襟副翼后几周她几乎不能运作。

吉布森飞往留尼旺,在他的海滩上找到约翰尼·贝格。 Bègue很友好。他向吉布森展示了他在哪里找到了襟副翼。吉布森四处寻找其他碎片,但没有期待,因为法国政府已经进行了后续搜索无济于事。 Flotsam需要一段时间才能穿越印度洋,在南部低纬度地区从东向西移动,并且襟副翼可能比其他碎片更早到达,因为它的一部分可以从水面上升起并充当帆。

留尼旺的一名报纸记者采访了吉布森有关这位独立美国调查员访问的故事。吉布森穿了一件 搜索 适合场合的T恤。然后他飞往澳大利亚,在那里他与两位海洋学家 – 珀斯西澳大利亚大学的Charitha Pattiaratchi和在霍巴特的政府研究中心工作的David Griffin进行了交谈,并被分配到澳大利亚运输安全局,寻找MH370的牵头机构。两人都是印度洋流和风的专家。格里芬特别花了数年时间跟踪漂浮浮标,并且已经开始努力模拟掠夺者在其离开留尼旺岛期间的复杂漂移特征 – 希望能够回溯并缩小海底搜索的地理范围。吉布森的需求更容易处理:他想知道浮动碎片上岸的最可能位置。答案是马达加斯加的东北海岸,以及较小程度上的莫桑比克海岸。

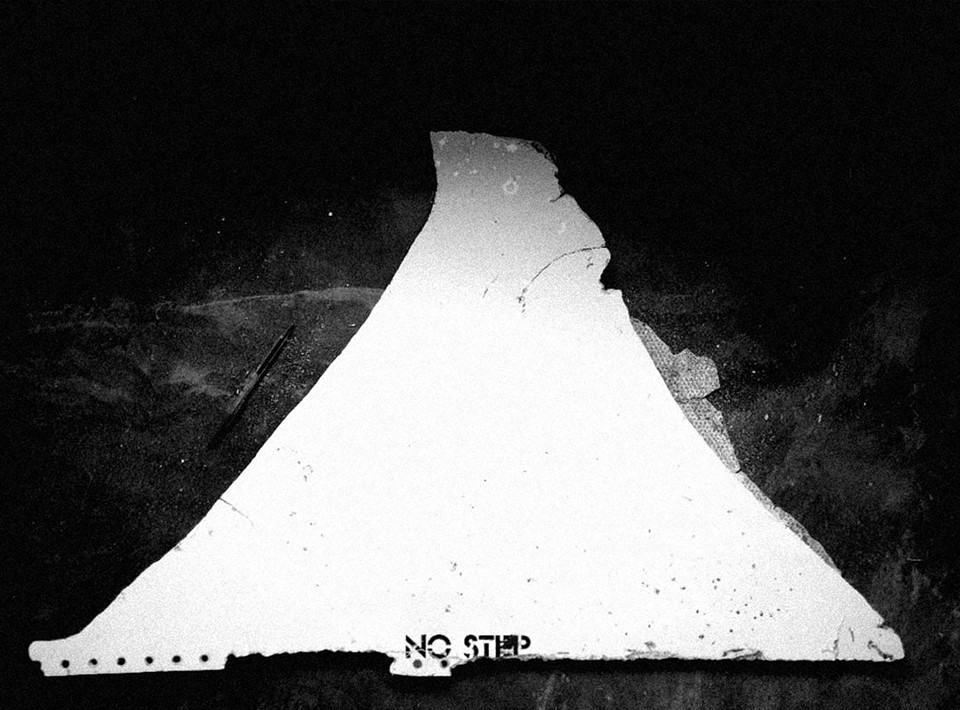

吉布森之所以选择莫桑比克,是因为他以前没有去过莫桑比克,可以把它作为他的第177个国家。他选择了一个叫Vilanculos的小镇,因为它看起来很安全并且拥有漂亮的海滩。他于2016年2月到达那里。他回忆说,他向当地渔民征求意见,并被告知有一个名为Paluma的沙洲,它位于珊瑚礁之外,渔民会去那里收集从印度洋冲洗过的渔网和浮标。吉布森支付了一名名叫苏莱曼的船夫将他带到那里。他们发现了各种各样的垃圾,主要是塑料。苏莱曼打电话给吉布森。他拿着一个约两英尺的灰色三角形废料,问道:“这是370吗?”废料有一个蜂窝结构和钢印字样 没有一步 在一个表面上。吉布森的第一印象是它不可能来自一架大型飞机。他说,“所以我的思绪告诉我这不是从飞机上来的,但是我的心在告诉我它是从飞机上来的。然后我们不得不把船拉回来。在这里,我们进入个人的事情。两只海豚出现并帮助我们离开沙洲 – 我母亲的精神动物。当我看到那些海豚时,我想, 这是从飞机上来的“。

做到这一点,但吉布森证明是对的。来自水平稳定器面板的废料几乎肯定来自MH370。吉布森飞往首都马普托,将碎片递给了澳大利亚领事。然后他飞到吉隆坡,正好赶上二周年纪念活动。这次他作为朋友受到了欢迎。

2016年6月,吉布森将注意力转移到马达加斯加偏远的东北海岸。事实证明这是母亲。吉布森说他第一天发现了三件,几天后又发现了两件。接下来的一周,在八英里外的海滩上,还有三件被运送给他。从那时起它就一直存在。有消息说,他将支付MH370碎片的费用。他说他曾经付过这么多钱 – 40美元 – 整个村庄都进行了为期一天的弯曲。显然当地的朗姆酒很便宜。

很多碎片被冲毁,与飞机无关。但是,迄今为止已确定的几十件可能是某些或可能或怀疑来自MH370,Gibson一直负责发现大约三分之一。有些作品仍在调查中。吉布森的影响力如此之大,以至于大卫格里芬虽然感激他,却担心所感知的碎片模式现在可能在统计上偏向马达加斯加,可能是以更远的北方点为代价。他给这个担心起了一个名字:“吉布森效应。”

事实仍然是,五年之后,没有人能够从碎片冲上岸的地方倒退,并将其追溯到印度洋南部的某个地方。在坚持保持开放思想的过程中,吉布森仍然希望能够找到新的碎片来解释消失的烧焦布线,例如火灾,或弹片上的火箭弹导弹 – 尽管已知的是航班的最后时间在很大程度上排除了这种可能性。 Gibson对这么多碎片的发现证实,信号分析是正确的。飞机飞了六个小时,直到飞机突然结束。控制器上的人没有努力轻轻地将飞机拉下来。它破灭了。吉布森认为,仍然有机会在一个瓶子里找到相当于一条信息的信息 – 一个人在他或她最后时刻在注定要失败的飞机上潦草地写下的绝望信。在海滩上,吉布森找到了几个背包和大量的钱包,所有这些都是空的。他说,最接近找到这样一张纸条的是一条用马来语写在棒球帽下面的信息。翻译,它写道,“它可能关注谁。我亲爱的朋友,稍后在宾馆见我。“

一个2014年3月8日晚上1点21分: 在南中国海上,靠近马来西亚和越南之间的航行航路点,MH370从空中交通管制雷达下降并转向西南,回到马来半岛。

乙– 大约一个小时后:

在飞越马六甲海峡西北方向后,这架飞机让调查人员称之为“最后一次大转弯”并向南飞去。转弯和新航线后来从卫星数据重建。

C– 2014年4月:

表面搜索被放弃,深海搜索正在进行中。对卫星数据的分析已经确定了MH370沿弧线的最终电子“握手”。

d– 2015年7月:

在留尼汪岛上发现了MH370的第一块碎片 – 襟副翼。在印度洋西部广泛分散的海滩上发现了其他确认或可能的碎片(红色的位置)。

4.阴谋

三项官方调查 在MH370失踪之后发射。第一个是最大,最严格,最昂贵的:技术先进的澳大利亚水下搜索工作,专注于定位主要碎片,以便检索飞机的飞行数据和驾驶舱语音记录器。它涉及飞机性能的计算,雷达和卫星记录的分析,海洋漂移的研究,统计分析的剂量以及东非漂浮物的体检 – 其中大部分来自布莱恩吉布森。它需要在世界上最汹涌的海域进行大规模的海上作战。协助这项工作的是志愿工程师和科学家的集合,他们在互联网上相互发现,称自己为独立小组,并且如此有效地合作,澳大利亚人将他们的工作考虑在内,并最终正式感谢他们的见解。在事故调查的史册中,这从未发生过。尽管如此,经过三年多的时间和大约1.6亿美元,澳大利亚的调查结果却没有成功。该公司于2018年被一家名为Ocean Infinity的美国公司收购,该公司与马来西亚政府签订了“无法找到,免费”的合同。这次搜索使用了先进的水下监视车辆,并覆盖了第七弧的一个新部分,这一部分被独立集团认为最有可能带来结果。几个月后,它也以失败告终。

第二次正式调查属于马来西亚警方,相当于飞机上的每个人以及他们的一些朋友的背景调查。很难知道警方发现的真实程度,因为调查所得的报告没有完全披露。该报告被秘密盖章,甚至还被其他马来西亚调查人员扣留,但在内部有人泄露之后,其不足之处变得清晰起来。特别是,它继续泄露所有关于船长Zaharie的知识。没有人感到惊讶。当时的总理是一个名叫Najib Razak的讨厌的人,据称他是一个极其腐败的人。马来西亚的新闻媒体受到审查。麻烦制造者被捡起并消失。官员们有理由谨慎行事。他们有事业要保护,也许还有他们的生命。显而易见的是,决定不追求可能在马来西亚航空公司或政府上反映不佳的某些途径。

第三次正式调查是事故调查,意图不是裁定责任,而是寻找可能的原因,并根据国际团队的最高全球标准进行。它是由马来西亚政府组建的一个特设工作组领导的,从一开始就是一团糟。警察和军方蔑视它。政府部长认为这是一种风险。被派去协助的外国专家几乎在他们到达时就开始撤退。一位美国专家,指的是应该管理事故调查的国际航空协议,他告诉我,“附件13是针对有信心的民主国家的事故调查而定制的,但在马来西亚这样的国家,有不安全和专制的官僚机构,以及航空公司无论是政府拥有的还是被视为国家声望的问题,它总是让人感到非常不合适。“

MH370进程的密切观察者说:“很明显,马来西亚人的主要目标是使这个主题消失。从一开始就有这种本能的偏见反对公开和透明,不是因为他们隐藏着一些深刻的,黑暗的秘密,而是因为他们不知道真相究竟在哪里,而且他们担心会出现令人尴尬的事情。 。他们掩盖了吗?是。他们掩盖了未知。“

最后,调查产生了一份495页的报告,模仿附件13的要求。它充满了777系统的样板描述,这些系统显然是从波音手册中解放出来的,没有任何技术价值。实际上,报告中的任何内容都没有技术价值,因为澳大利亚的出版物已经完全涵盖了相关的卫星信息和海洋漂移分析。马来西亚的报告被视为粉饰,其唯一真正的贡献是对空中交通管制失败的坦率描述 – 大概是因为其中一半可归咎于越南人,而且因为马来西亚控制人员构成了当地最弱的目标, 政治上。该报告于2018年7月发布,比事件发生四年多。它表示调查小组无法确定飞机失踪的原因。

这样的结论会引发持续的猜测,即使这是无根据的。 The satellite data provide the best evidence of the airplane’s flight path, and are hard to argue with, but people have to have trust in numbers to accept the story they tell. All sorts of theorists have made claims, amplified by social media, that ignore the satellite data, and in some cases also the radar tracks, the aircraft systems, the air-traffic-control record, the physics of flight, and the basic contours of planetary geography. For example, a British woman who blogs under the name of Saucy Sailoress and does Tarot readings for hire was vagabonding around southern Asia with her husband and dogs in an oceangoing sailboat. She says that on the night MH370 disappeared they were in the Andaman Sea, and she spotted what looked like a cruise missile coming at her. The missile morphed into a low-flying airplane with a well-lit cockpit, bathed in a strange orange glow and trailing smoke. As it flew by she concluded that it was on a suicide mission against a Chinese naval fleet farther out to sea. She did not yet know about the disappearance of MH370, but when, a few days later, she learned of it she drew what was to her the obvious connection. Implausible, perhaps, but she gained an audience.

An Australian has been claiming for several years to have found MH370 by means of Google Earth, in shallow waters and intact; he has refused to disclose the location while he works on crowdfunding an expedition. On the internet you will find claims that the airplane has been found intact in the Cambodian jungle, that it was seen landing in an Indonesian river, that it flew into a time warp, that it was sucked into a black hole. One scenario has the airplane flying off to attack the American military base on Diego Garcia before getting shot down. A recent online report that Captain Zaharie had been discovered alive and was lying in a Taiwanese hospital with amnesia won sufficient acceptance that Malaysia angrily denied it. The news had come from a crudely satirical website that also reported a sexual assault on an American trekker and two Sherpas by a yeti-like creature in Nepal.

A New York–based writer named Jeff Wise has hypothesized that one of the electronic systems on board the airplane may have been reprogrammed to provide false data—indicating a turn south into the Indian Ocean when in fact the airplane turned north toward Kazakhstan—in order to lead investigators astray. He calls this the “spoof” scenario, and has elaborated extensively on it, most recently in a 2019 ebook. He proposes that the Russians might have stolen the airplane to create a distraction from the annexation of Crimea, then under way. An obvious weak spot in the argument is the need to explain how, if the airplane was flown to Kazakhstan, all that wreckage ended up in the Indian Ocean. Wise’s answer is that it was planted.

Blaine Gibson was new to social media when he started his search, and he was in for a surprise. As he recalls, the trolls emerged as soon as he found his first piece—the one labeled no step—and they multiplied afterward, particularly as the beaches of Madagascar began to bear fruit. The internet provokes emotion even in response to unremarkable events. A catastrophe taps into something toxic. Gibson was accused of exploiting the families and of being a fraud, a publicity hound, a drug addict, a Russian agent, an American agent, and at the very least a dupe. He began receiving death threats—messages on social media and phone calls to friends predicting his demise. One message said that either he would stop looking for debris or he would leave Madagascar in a coffin. Another warned that he would die of polonium poisoning. There were more. He was not prepared for this, and was incapable of shrugging it off. During the days I spent with him in Kuala Lumpur, he kept abreast of the latest attacks with the assistance of a friend in London. He said, “I once made the mistake of going on Twitter. Basically, these people are cyberterrorists. And it works. It’s effective.” He has been traumatized.

In 2017, Gibson arranged a formal mechanism for the transfer of debris: He would turn over any new find to authorities in Madagascar, who would hand it to Malaysia’s honorary consul, who would pack it up and ship it to Kuala Lumpur for examination and storage. On August 24 of that year, the honorary consul was gunned down in his car by an assassin who escaped on a motorcycle and has never been found. A French-language news account alleged that the consul had a shady past; his killing may have had no connection to MH370 at all. Gibson, however, has assumed that there is a connection. A police investigation is ongoing.

By now he largely avoids disclosing his location or travel plans, and for similar reasons avoids using email and rarely speaks over the telephone. He likes Skype and WhatsApp for their encryption. He frequently swaps out his SIM cards. He believes he is sometimes followed and photographed. There is no arguing that Gibson is the only person who has gone out looking for pieces of MH370 on his own and found debris. But the idea that the debris is worth killing for is hard to take seriously. It would be easier to believe if the debris held clues to dark secrets and international intrigue. But the evidence—much of it now out in the open—points in a different direction.

5. The Possibilities

In truth, a 批量 can now be known with certainty about the fate of MH370. First, the disappearance was an intentional act. It is inconceivable that the known flight path, accompanied by radio and electronic silence, was caused by any combination of system failure and human error. Computer glitch, control-system collapse, squall lines, ice, lightning strike, bird strike, meteorite, volcanic ash, mechanical failure, sensor failure, instrument failure, radio failure, electrical failure, fire, smoke, explosive decompression, cargo explosion, pilot confusion, medical emergency, bomb, war, or act of God—none of these can explain the flight path.

Second, despite theories to the contrary, control of the plane was not seized remotely from within the electrical-equipment bay, a space under the forward galley. Pages could be spent explaining why. Control was seized from within the cockpit. This happened in the 20-minute period from 1:01 a.m., when the airplane leveled at 35,000 feet, to 1:21 a.m., when it disappeared from secondary radar. During that same period, the airplane’s automatic condition-reporting system transmitted its regular 30-minute update via satellite to the airline’s maintenance department. It reported fuel level, altitude, speed, and geographic position, and indicated no anomalies. Its transmission meant that the airplane’s satellite-communication system was functioning at that moment.

By the time the airplane dropped from the view of secondary—transponder-enhanced—radar, it is likely, given the implausibility of two pilots acting in concert, that one of them was incapacitated or dead, or had been locked out of the cockpit. Primary-radar records—both military and civilian—later indicated that whoever was flying MH370 must have switched off the autopilot, because the turn the airplane then made to the southwest was so tight that it had to have been flown by hand. Circumstances suggest that whoever was at the controls deliberately depressurized the airplane. At about the same time, much if not all of the electrical system was deliberately shut down. The reasons for that shutdown are not known. But one of its effects was to temporarily sever the satellite link.

An electrical engineer in Boulder, Colorado, named Mike Exner, who is a prominent member of the Independent Group, has studied the radar data extensively. He believes that during the turn, the airplane climbed up to 40,000 feet, which was close to its limit. During the maneuver the passengers would have experienced some g‑forces—that feeling of being suddenly pressed back into the seat. Exner believes the reason for the climb was to accelerate the effects of depressurizing the airplane, causing the rapid incapacitation and death of everyone in the cabin.

An intentional depressurization would have been an obvious way—and probably the only way—to subdue a potentially unruly cabin in an airplane that was going to remain in flight for hours to come. In the cabin, the effect would have gone unnoticed but for the sudden appearance of the drop-down oxygen masks and perhaps the cabin crew’s use of the few portable units of similar design. None of those cabin masks was intended for more than about 15 minutes of use during emergency descents to altitudes below 13,000 feet; they would have been of no value at all cruising at 40,000 feet. The cabin occupants would have become incapacitated within a couple of minutes, lost consciousness, and gently died without any choking or gasping for air. The scene would have been dimly lit by the emergency lights, with the dead belted into their seats, their faces nestled in the worthless oxygen masks dangling on tubes from the ceiling.

The cockpit, by contrast, was equipped with four pressurized-oxygen masks linked to hours of supply. Whoever depressurized the airplane would have simply had to slap one on. The airplane was moving fast. On primary radar it appeared as an unidentified blip approaching the island of Penang at nearly 600 miles an hour. The mainland nearby is home to Butterworth Air Base, where a squadron of Malaysian F-18 interceptors is stationed, along with an air-defense radar—not that anyone was paying attention. According to a former official, before the accident report was released last summer, Malaysian air-force officers demanded to review and edit it. In a section called “Malaysian Military Radar,” the report provides a timeline suggesting that the air-defense radar had been actively monitored, that the military was well aware of the identity of the aircraft, and that it purposefully “did not pursue to intercept the aircraft since it was ‘friendly’ and did not pose any threat to national airspace security, integrity and sovereignty.” The question of course is why, if the military knew the airplane had turned around and was flying west, it then allowed the search to continue for days in the wrong body of water, to the east.

For all its expensive equipment, the air force had failed at its job and could not bring itself to admit the fact. In an Australian television interview, the former Malaysian defense minister said, “If you’re not going to shoot it down, what’s the point in sending (an interceptor) up?” Well, for one thing, you could positively identify the airplane, which at this point was just a blip on primary radar. You could also look through the windows into the cockpit and see who was at the controls.

At 1:37 a.m., MH370’s regularly scheduled 30-minute automatic condition-reporting system failed to transmit. We now know that the system had been isolated from any satellite transmission—something easily done from within the cockpit—and therefore could not send out any of its scheduled reports.

At 1:52 a.m., half an hour into the diversion, MH370 passed just south of Penang Island, made a wide right turn, and headed northwest up the Strait of Malacca. As the airplane turned, the first officer’s cellphone registered with a tower below. It was a single brief connection, during which no content was transmitted. Eleven minutes later, on the assumption that MH370 was still over the South China Sea, a Malaysia Airlines dispatcher sent a text message instructing the pilots to contact Ho Chi Minh’s air-traffic-control center. The message went unanswered. All through the Strait of Malacca, the airplane continued to be hand-flown. It is presumed that everyone in the cabin was dead by this point. At 2:22 a.m., the Malaysian air-force radar picked up the last blip. The airplane was 230 miles northwest of Penang, heading northwest into the Andaman Sea and flying fast.

Three minutes later, at 2:25, the airplane’s satellite box suddenly returned to life. It is likely that this occurred when the full electrical system was brought back up, and that the airplane was repressurized at the same time. When the satellite box came back on, it sent a log-on request to Inmarsat; the ground station responded, and the first linkup was accomplished. Unbeknownst to anyone in the cockpit, the relevant distance and Doppler values were recorded at the ground station, later allowing the first arc to be established. A few minutes later a dispatcher put in a phone call to the airplane. The satellite box accepted the link, but the call went unanswered. An associated Doppler value showed that the airplane had just made a wide turn to the south. To investigators, the place where this happened became known as the “final major turn.” Its location is crucial to all the efforts that have followed, but it has never quite been pinned down. Indonesian air-defense radar should have shown it, but the radar seems to have been turned off for the night.

MH370 was now most likely flying on autopilot, cruising south into the night. Whoever was occupying the cockpit was active and alive. Was this a hijacking? A hijacking is the “third party” solution favored in the official report. It is the least painful explanation for anyone in authority that night. It has immense problems, however. The main one is that the cockpit door was fortified, electrically bolted, and surveilled by a video feed that the pilots could see. Also, less than two minutes passed between Zaharie’s casual “good night” to the Kuala Lumpur controller and the start of the diversion, with the attendant loss of the transponder signal. How would hijackers have known to make their move precisely during the handoff to Vietnamese air traffic control, and then gained access so quickly and smoothly that neither of the pilots had a chance to transmit a distress call? It is possible of course that the hijackers were known to the pilots—that they were invited into the cockpit—but even that does not explain the lack of a radio transmission, particularly during the hand-flown turn away from Beijing. Both of the control yokes had transmitter switches, within the merest finger reach, and some signal could have been sent in the moments before an attempted takeover. Furthermore, every one of the passengers and cabin-crew members has been investigated and cleared of suspicion by teams of Malaysian and Chinese investigators aided by the FBI. The quality of that police work is open to question, but it was thorough enough to have uncovered the identities of two Iranians who were traveling under false names with stolen passports—seeking, however, nothing more nefarious than political asylum in Germany. It is possible that stowaways—by definition unrecorded on the airplane’s manifest—had hidden in the equipment bay. If so, they would have had access to two circuit breakers that, if pulled, would have unbolted the cockpit door. But that scenario has problems, too. The bolts click loudly when they open—an unambiguous sound that would have been familiar to the pilots. The hijackers would then have had to open a galley-floor hatch from below, climb a short ladder, evade notice by the cabin crew, evade the surveillance video, and enter the cockpit before either of the pilots transmitted a distress call. It is unlikely that this could have happened, just as it is unlikely that a flight attendant held hostage could have used the door keypad to allow sudden entry without firing off a warning. Furthermore, what would the purpose be of a hijacking? Money? Politics? Publicity? An act of war? A terrorist attack? The intricate seven-hour profile of MH370’s deviation into oblivion fits none of these scenarios. And no one has claimed responsibility for the act. Anonymity is not consistent with any of these motives.

6. The Captain

This leaves us with a different sort of event, a hijacking from within where no forced entry is required—by a pilot who runs amok. Reasonable people may resist the idea that a pilot would murder hundreds of innocent passengers as the collateral price of killing himself. The definitive response is that this has happened before. In 1997, a captain working for an Indonesian airline called SilkAir is believed to have disabled the black boxes of a Boeing 737 and to have plunged the airplane at supersonic speeds into a river. In 1999, EgyptAir Flight 990 was deliberately crashed into the sea by its co-pilot off the coast of Long Island, resulting in the loss of everyone on board. In 2013, just months before MH370 disappeared, the captain of LAM Mozambique Airlines Flight 470 flew his Embraer E190 twin jet from cruising altitude into the ground, killing all 27 passengers and all six crew members. The most recent case is the Germanwings Airbus that was deliberately crashed into the French Alps on March 24, 2015, also causing the loss of everyone on board. Its co-pilot, Andreas Lubitz, had waited for the pilot to use the bathroom and then locked him out. Lubitz had a record of depression and—as investigations later discovered—had made a study of MH370’s disappearance, one year earlier.

From the November 2001 issue: William Langewiesche on EgyptAir 990

In the case of MH370, it is difficult to see the co-pilot as the perpetrator. He was young and optimistic, and reportedly planning to get married. He had no history of any sort of trouble, dissent, or doubts. He was not a German signing on to a life in a declining industry of budget airlines, low salaries, and even lower prestige. He was flying a glorious Boeing 777 in a country where the national airline and its pilots are still considered a pretty big deal.

It is the captain, Zaharie, who raises concerns. The first warning is his portrayal in the official reports as someone beyond reproach—a good pilot and placid family man who liked to play with a flight simulator. This is the image promoted by Zaharie’s family, but it is contradicted by multiple indications of trouble that too obviously have been brushed over.

The police discovered aspects of Zaharie’s life that should have caused them to dig more deeply. The formal conclusions they drew were inadequate. The official account, referring to Zaharie as the PIC, or pilot in command, had this to say:

The PIC’s ability to handle stress at work was reported to be good. There was no known history of apathy, anxiety, or irritability. There were no significant changes in his lifestyle, interpersonal conflict, or family stresses … There were no behavioral signs of social isolation, change of habits or interest … On studying the PIC’s behavioral pattern on the CCTV (at the airport) on the day of the flight and prior 3 flights, there were no significant behavioral changes observed. On all the CCTV recordings the appearance was similar, i.e. well-groomed and attired. The gait, posture, facial expressions and mannerisms were his normal characteristics.

This was either irrelevant or at odds with what was knowable about Zaharie. The truth, as I discovered after speaking in Kuala Lumpur with people who knew him or knew about him, is that Zaharie was often lonely and sad. His wife had moved out, and was living in the family’s second house. By his own admission to friends, he spent a lot of time pacing empty rooms waiting for the days between flights to go by. He was also a romantic. He is known to have established a wistful relationship with a married woman and her three children, one of whom was disabled, and to have obsessed over two young internet models, whom he encountered on social media, and for whom he left Facebook comments that apparently did not elicit responses. Some were shyly sexual. He mentioned in one comment, for example, that one of the girls, who was wearing a robe in a posted photo, looked like she had just emerged from a shower. Zaharie seems to have become somewhat disconnected from his earlier, well-established life. He was in touch with his children, but they were grown and gone. The detachment and solitude that can accompany the use of social media—and Zaharie used social media a lot—probably did not help. There is a strong suspicion among investigators in the aviation and intelligence communities that he was clinically depressed.

If Malaysia were a country where, in official circles, the truth was welcome, then the police portrait of Zaharie as a healthy and happy man would carry some weight. But Malaysia is not such a country, and the official omission of evidence to the contrary only adds to all the other evidence that Zaharie was a troubled man.

Forensic examinations of Zaharie’s simulator by the FBI revealed that he experimented with a flight profile roughly matching that of MH370—a flight north around Indonesia followed by a long run to the south, ending in fuel exhaustion over the Indian Ocean. Malaysian investigators dismissed this flight profile as merely one of several hundred that the simulator had recorded. That is true, as far as it goes, which is not far enough. Victor Iannello, an engineer and entrepreneur in Roanoke, Virginia, who has become another prominent member of the Independent Group and has done extensive analysis of the simulated flight, underscores what the Malaysian investigators ignored. Of all the profiles extracted from the simulator, the one that matched MH370’s path was the only one that Zaharie did not run as a continuous flight—in other words, taking off on the simulator and letting the flight play out, hour after hour, until it reached the destination airport. Instead he advanced the flight manually in multiple stages, repeatedly jumping the flight forward and subtracting the fuel as necessary until it was gone. Iannello believes that Zaharie was responsible for the diversion. Given that there was nothing technical that Zaharie could have learned by rehearsing the act on a gamelike Microsoft consumer product, Iannello suspects that the purpose of the simulator flight may have been to leave a bread-crumb trail to say goodbye. Referring to the flight profile that MH370 would follow, Iannello said of Zaharie, “It’s as if he was simulating a simulation.” Without a note of explanation, Zaharie’s reasoning is impossible to know. But the simulator flight cannot easily be dismissed as a random coincidence.

In Kuala Lumpur, I met with one of Zaharie’s lifelong friends, a fellow 777 captain whose name I have omitted because of possible repercussions for him. He too believed that Zaharie was guilty, a conclusion he had come to reluctantly. He described the mystery as a pyramid that is broad at the base and one man wide at the top, meaning that the inquiry might have begun with many possible explanations but ended up with a single one. He said, “It doesn’t make sense. It’s hard to reconcile with the man I knew. But it’s the necessary conclusion.” I asked about the need Zaharie would have had to somehow deal with his cockpit companion, First Officer Fariq Hamid. He replied, “That’s easy. Zaharie was an examiner. All he had to say was ‘Go check something in the cabin,’ and the guy would have been gone.” I asked about a motive. He had no idea. He said, “Zaharie’s marriage was bad. In the past he slept with some of the flight attendants. And so what? We all do. You’re flying all over the world with these beautiful girls in the back. But his wife knew.” He agreed that this was hardly a reason to go berserk, but thought Zaharie’s emotional state might have been a factor.

Does the absence of all of this from the official report— Zaharie’s travails; the peculiar nature of the flight profile on the simulator—not to mention the technical inadequacies of the report itself, constitute a cover-up? At this point, we cannot say. We know some of what the investigators knew but chose not to reveal. There is likely more that they discovered and that we do not yet know.

Which brings us back to the demise of MH370. It is easy to imagine Zaharie toward the end, strapped into an ultra-comfortable seat in the cockpit, inhabiting his cocoon in the glow of familiar instruments, knowing that there could be no return from what he had done, and feeling no need to hurry. He would long since have repressurized the airplane and warmed it to the right degree. There was the hum of the living machine, the beautiful abstractions on the flatscreen displays, the carefully considered backlighting of all the switches and circuit breakers. There was the gentle 嗖 of the air rushing by. The cockpit is the deepest, most protective, most private sort of home. Around 7 a.m., the sun rose over the eastern horizon, to the airplane’s left. A few minutes later it lit the ocean far below. Had Zaharie already died in flight? He could at some point have depressurized the airplane again and brought his life to an end. This is disputed and far from certain. Indeed, there is some suspicion, from fuel-exhaustion simulations that investigators have run, that the airplane, if simply left alone, would not have dived quite as radically as the satellite data suggest that it did—a suspicion, in other words, that someone was at the controls at the end, actively helping to crash the airplane. Either way, somewhere along the seventh arc, after the engines failed from lack of fuel, the airplane entered a vicious spiral dive with descent rates that ultimately may have exceeded 15,000 feet a minute. We know from that descent rate, as well as from Blaine Gibson’s shattered debris, that the airplane disintegrated into confetti when it hit the water.

7. The Truth

For now the official investigations have petered out. The Australians have done what they could. The Chinese want to move on and are censoring any news that might inflame the passions of the families. The French are off in France, rehashing the satellite data. The Malaysians just wish the whole subject would go away. I attended an event in the administrative city of Putrajaya last fall, where Grace Nathan and Gibson stood in front of the cameras with the transport minister, Anthony Loke. The minister formally accepted five new pieces of debris collected over the summer. He was miserable to the point of being angry. He barely spoke, and took no questions from the press. Nathan was seething at the minister’s attitude. That night, over dinner, she insisted that the government should not be allowed to walk away so easily. She said, “They didn’t follow protocol. They didn’t follow procedure. I think it’s appalling. More could have been done. As a result of the inaction of the air force—of all of the parties involved in the first hour who didn’t follow protocol—we are stuck like this now. Every one of them breached protocol one time, multiple times. Every single person who had some form of responsibility at the time did not do what he was supposed to do. To varying degrees of severity. Maybe in isolation some might not seem so bad, but when you look at it as a whole, every one of them contributed 100 percent to the fact that the airplane has not been found.”

And every one of them was a government employee. Nathan had hopes that Ocean Infinity, which had recently found a missing Argentine submarine, would return to the search, again on a no-find, no-fee basis. The company had suggested the possibility of doing so earlier that week. But the government of Malaysia would have to sign the contract. Because of the political culture, Nathan worried that it might not—as so far has proved true.

If the wreckage is ever found, it will lay to rest all the theories that depend on ignoring the satellite data or the fact that the airplane flew an intricate path after its initial turn away from Beijing and then remained aloft for six more hours. No, it did not catch on fire yet stay in the air for all that time. No, it did not become a “ghost flight” able to navigate and switch its systems off and then back on. No, it was not shot down after long consideration by nefarious national powers who lingered on its tail before pulling the trigger. And no, it is not somewhere in the South China Sea, nor is it sitting intact in some camouflaged hangar in Central Asia. The one thing all of these explanations have in common is that they contradict the authentic information investigators do possess.

That aside, finding the wreckage and the two black boxes may accomplish little. The cockpit voice recorder is a self-erasing two-hour loop, and is likely to contain only the sounds of the final alarms going off, unless whoever was at the controls was still alive and in a mood to provide explanations for posterity. The other black box, the flight-data recorder, will provide information about the functioning of the airplane throughout the entire flight, but it will not reveal any relevant system failure, because no such failure can explain what occurred. At best it will answer some relatively unimportant questions, such as when exactly the airplane was depressurized and how long it remained so, or how exactly the satellite box was powered down and then powered back up. The denizens of the internet would be obsessed, but that is hardly an event to look forward to.

The important answers probably don’t lie in the ocean but on land, in Malaysia. That should be the focus moving forward. Unless they are as incompetent as the air force and air traffic control, the Malaysian police know more than they have dared to say. The riddle may not be deep. That is the frustration here. The answers may well lie close at hand, but they are more difficult to retrieve than any black box. If Blaine Gibson wants a real adventure, he might spend a year poking around Kuala Lumpur.

This article appears in the July 2019 print edition with the headline “‘Good Night. Malaysian Three-Seven-Zero.’”

_20240517160213_theedgemalaysia.jpg)